Pelvic Organ Prolapse

What Is Pelvic Organ Prolapse?

Pelvic organ prolapse is a type of hernia, which occurs when part of an organ protrudes through an abnormal opening in the muscle or tissue that surrounds it. In pelvic organ prolapse, the connective tissue and pelvic floor muscles that support the pelvic organs (uterus, vagina, bladder, bowels and rectum) become weak or tear, so these organs move out of their normal position.

If you have pelvic organ prolapse, you may feel a bulge near your vagina or the vagina drop down outside of your body. It may take many years after your pelvic floor is damaged before you feel a bulge. Up to one-third of women develop bothersome pelvic organ prolapse before age 80.

The urogynecologic surgeons at the University of Chicago Medicine are at the forefront of cutting-edge surgical care and research for women with pelvic organ prolapse. We work with you to develop a personalized treatment plan based on your type of prolapse, genetics, lifestyle and goals for treatment.

All of our urogynecologic surgeons completed fellowship training and received board certification in female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery from the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

You will also have access to groundbreaking national clinical research trials through our team’s participation in the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network.

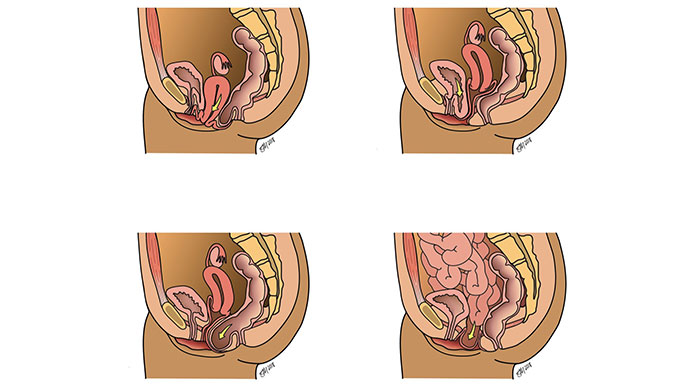

Types of Pelvic Organ Prolapse

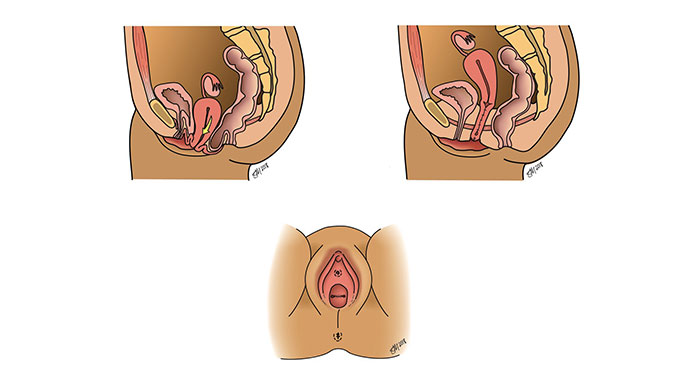

- Uterine prolapse: The uterus drops into the vaginal canal or bulges through the vaginal opening.

- Anterior vaginal wall prolapse (cystocele): The front wall of the vagina sags allowing the bladder to drop into the vagina or past the vaginal opening.

- Posterior vaginal wall prolapse (rectocele/enterocele): The back wall of the vagina pouches forward, allowing the rectum or intestines to bulge into the vagina or past the vaginal opening.

- Vaginal vault prolapse: The vaginal walls weaken after a woman has a hysterectomy, causing the top of the vagina to bulge into the canal or past the vaginal opening.

Pelvic Organ Prolapse Symptoms

If you have pelvic organ prolapse, you may have one or more of the following symptoms:

- Bulging tissue from the vaginal opening

- Pelvic pressure

- Difficulty urinating, such as a slow stream or the need to push on the bulge to empty your bladder

- Difficulty having a bowel movement and needing to press on the bulge to empty the bowel, or feeling like stool is trapped near the opening of the anus

What Causes Pelvic Organ Prolapse?

Pregnancy and childbirth are the most common risk factors for prolapse. Childbirth can damage the muscles and ligaments that support the pelvic organs. Each pregnancy and delivery increases your chance of having prolapse. Having an assisted vaginal delivery (operative vaginal delivery with forceps) or a large baby also raise your risk for pelvic organ prolapse.

In addition to pregnancy and childbirth, other causes of pelvic organ prolapse include:

- Chronic coughing, constipation, obesity and heavy lifting, which put pressure on the pelvic floor and weaken the muscles

- Menopause, which is associated with a decrease in estrogen levels causing weakening of the supportive tissues in the pelvis

- Aging

- Genetics, which determine the strength of the connective tissue in your pelvis; if your mother or sister had pelvic organ prolapse, you have a higher risk for developing prolapse

Diagnosing Pelvic Organ Prolapse

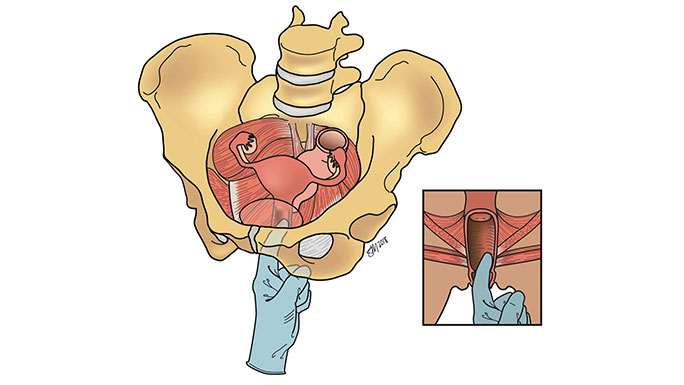

During your office visit, your urogynecologic surgeon will examine your pelvic floor muscle function as well as your pelvic support. Your surgeon may suggest additional tests to better understand your anatomy and how well your pelvic organs work. These include:

- Post-void residual urine test to determine how well you empty your bladder. Many women have difficulty emptying their bladder because the location of their bladder has shifted, and they might not even know it. This puts them at risk for urinary tract infections and other conditions that could damage the urinary tract. When you have this test, you empty your bladder, and then a tiny sterile catheter is placed into your urethra to drain your bladder. The urine volume is measured, and a sample is sent to the lab to check for a urinary tract infection or other conditions.

- Urodynamic testing to assess the function of your bladder and urethra. Many women with prolapse can also have lower urinary tract symptoms including frequent urination, difficulty urinating or urinary incontinence. This test can help reveal why you are having symptoms.

Pelvic Organ Prolapse Treatment

Nonsurgical Treatment Options

Nonsurgical and surgical treatments are available for pelvic organ prolapse. You and your urogynecologist will discuss all options to help achieve your health goals.

Pelvic organ prolapse is not a life-threatening condition. If you do not have discomfort or other symptoms that affect your quality of life, you may choose to have us monitor the prolapse over time. It’s possible that your condition could stay the same, or it could worsen over time. If you choose this option, it is important to stay in contact with your urogynecologist.

Some lifestyle changes can either slow the progression of prolapse or treat other conditions associated with prolapse. It may help if you:

- Add fiber to your diet to treat constipation and reduce straining during bowel movements.

- Stop smoking, which doubles your risk for developing a pelvic floor disorder.

- Maintain a healthy weight or lose weight if you are overweight.

Pelvic floor physical therapy helps the muscles in your pelvic floor, abdomen, back and diaphragm (the muscle barrier that separates the chest from the abdomen) work properly.

Your physical therapist might recommend biofeedback, a technique that helps you become more aware of your body’s functions so you can control them. In urology and gynecology, biofeedback is typically used to help women locate and strengthen their pelvic floor muscles.

During biofeedback therapy, special measuring devices are placed in your vagina, rectum or on your skin to monitor your pelvic floor. You will then contract your pelvic muscles while watching the strength of each contraction on a computer screen. This interactive approach allows you to adjust each pelvic floor squeeze to make it stronger and more effective.

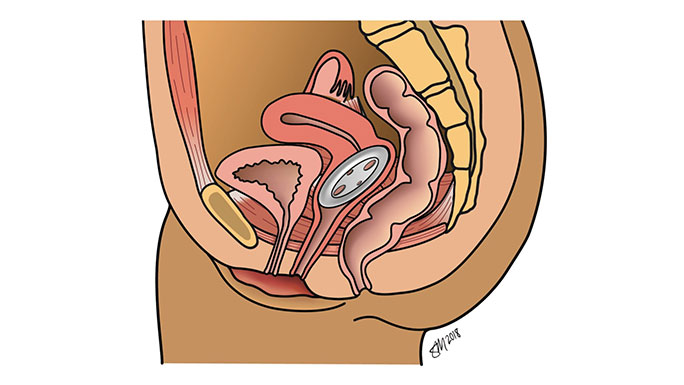

A pessary is a small silicone device inserted into the vagina to support the organs above the pelvic floor muscles to prevent tissue from bulging out of the vagina.

Minimally Invasive Surgery for Pelvic Organ Prolapse

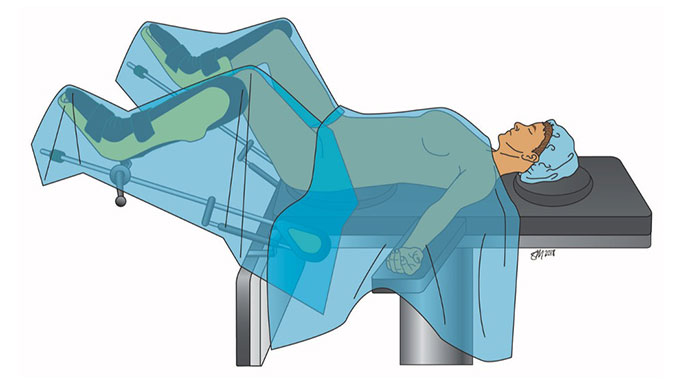

Many women who are bothered by symptoms of prolapse will choose to have surgery to correct their prolapse. The goal of surgery is to re-support the walls of the vagina to eliminate the bulging of tissue. At UChicago Medicine, your urogynecologic surgeon will offer a range of minimally invasive procedures for pelvic organ prolapse. These procedures are performed as same-day surgeries and are associated with minimal downtime.

There are several different surgical options, each with different routes and materials to suspend the vagina. The decision to proceed with one procedure over another will be made with you and your urogynecologic surgeon, but it is complex, and it is important to understand that you are not alone. The urogynecologists at UChicago Medicine recognize this and have pioneered a computer-based decision-making module to assist women with this decision based on their values and treatment goals. During your consultation, you’ll receive an introduction to your surgical options and will be provided access to this computer-based module that provides educational materials. Your results from the module will serve as a starting point for your next discussion with your surgeon. During that next appointment, our goal is to answer all your questions so you can choose the best option for you.

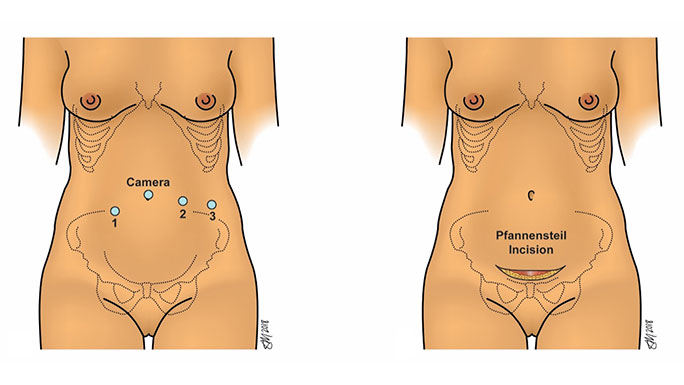

Types of minimally invasive surgery for pelvic organ prolapse:

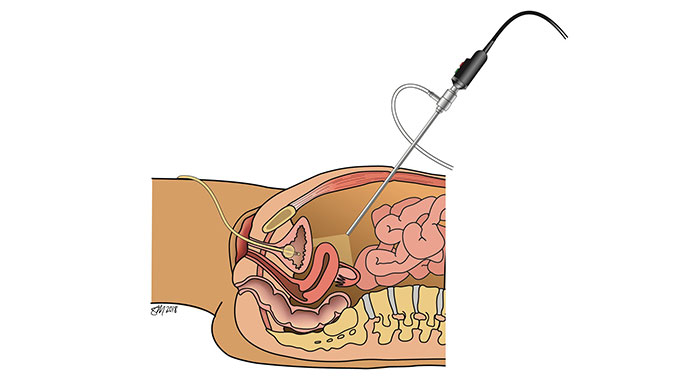

Sacrocolpopexy repairs vaginal or uterovaginal prolapse by restoring the support of the vagina and reinforcing the repair with a hernia mesh. This is the most durable option for patients with prolapse.

For women with vaginal or uterovaginal prolapse, sacrospinous ligament suspension surgery restores the support of the vagina using the patient’s own tissues.

Uterosacral ligament suspension is for women with vaginal vault or uterovaginal prolapse. Like sacrospinous ligament suspension surgery, uterosacral ligament suspension surgery also uses the patient’s own tissues to support the vagina.

Similar to a sacrocolpopexy but instead of a synthetic mesh, the top of the vagina is attached with stitches to supportive ligaments in the pelvis. Because mesh is not used, the results may not last as long as a sacrocolpopexy.

A small incision is made in the vagina, and a urogynecologic surgeon uses stitches and your own tissue to attach the top of the vagina to ligaments in the pelvis and/or along the sacral spine. Most patients go home the same day of surgery with minimal pain and a short recovery time. Because mesh is not used in this procedure, it is a less durable option for women with prolapse.

For women who do not plan to have vaginal intercourse in the future, a colpocleisis has an extremely high success rate and can prevent future pelvic organ prolapse.

These prolapse surgeries can be performed while maintaining the uterus, fallopian tubes and ovaries. Or if a patient chooses, these procedures can be done at the same time as a hysterectomy to remove the uterus, fallopian tubes and/or ovaries.

Some women with pelvic organ prolapse may have another pelvic floor disorder they don’t know about. Your urogynecologic surgeon will talk to you about evaluating your risk for unmasking stress incontinence at the time of surgery through (optional) additional testing. Based on those results, you can choose to have an additional incontinence procedure performed at the same time as any of the surgical procedures to address prolapse.

Pelvic Organ Prolapse Surgery Recovery

Having minimally invasive surgery for pelvic organ prolapse does not necessarily involve a lengthy recovery. As part of UChicago Medicine’s Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) initiative, we often do not restrict physical activity for women who recently had surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. In fact, studies led by our urogynecologic surgeons have shown that women who return to their usual activities and exercise when they feel up to it have better surgical outcomes and a higher quality of life compared with women who have activity restrictions after surgery.

Meet Our Urogynecologists

Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery

Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery

Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery

Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery

Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery