Revitalized transplant program aims to make more lifesaving organ transplants possible

.jpg&w=3840&q=75)

It was a stunning sequence of events, even for an institution accustomed to historic achievements. In a span of less than two days, surgeons completed two separate triple-organ transplants at the University of Chicago Medicine. The two 29-year-old patients, Sarah McPharlin of Grosse Pointe Woods, Michigan, and Daru Smith of Chicago, each received a heart, liver and kidney.

Smith’s surgery began at 3:07 p.m. on Dec. 19. McPharlin’s commenced at 6:04 p.m. the next day, just 27 hours later. According to federal statistics, it was the first time a U.S. hospital had ever performed more than one of these complex procedures within one year.

“We never in our wildest dreams imagined both would take place at virtually the same time,” said John Fung, PhD, MD, a transplant surgeon and co-director of the UChicago Medicine Transplant Institute. “Pulling this off can feel like trying to perform a high-wire ballet in the middle of running a marathon. But we were always confident in our patients as well as our team’s abilities.”

These cases are the 16th and 17th times this type of triple-organ transplant has been performed in this country — and six of those surgeries were at UChicago Medicine. No other institution in the world has performed more of these multi-organ procedures.

Perhaps no other institution has such a rich history of achievements in organ transplantation, but on the heels of two of its most extraordinary cases, the Transplant Institute is looking to the future. With new leadership and an innovative new structure, the institute hopes to expand the range of organs and tissues it can transplant, the types of donor organs it can accept and which patients can receive them, making the lifesaving gift of organ transplants available to as many patients as possible.

A history of breakthroughs

Organ transplantation began at the University of Chicago. Alexis Carrel, MD, a pioneer in cardiac surgery, developed the technique for joining severed ends of blood vessels together that made organ transplantation possible. He performed the first heart transplant, on a dog, at UChicago in 1904. The dog survived for two hours. In 1912, Carrel received the first Nobel Prize awarded in physiology or medicine for work done in America.

Christoph Broelsch, MD, performed the first liver transplant using a segment of a cadaver liver in the U.S. at UChicago in 1985. He also performed the first split-liver transplant, using one donor for two recipients, in the U.S. in 1988 and developed the technique for transplantation from a living donor. Broelsch’s team then performed the first successful living-donor liver transplant in the world at UChicago in November 1989, and, in 1993, a UChicago team performed the first liver transplant from an unrelated living donor, a close family friend of a 9-year-old boy with cystic fibrosis whose relatives were medically ineligible to donate.

Other advances expanded the opportunities for patients to receive an organ transplant. In 1997, a team led by ethicist Lainie Friedman Ross, assistant professor of pediatrics and associate director of the MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics at the time, proposed the first paired kidney exchange program, which would allow two people who need kidney transplants and have willing but incompatible donors to exchange donor kidneys. Their protocol, published in The New England Journal of Medicine, was adapted for wider use and helped make possible nationwide exchanges involving many donors and recipients.

The breakthroughs continued to accumulate through the 1990s and into the current century, with several multiple-organ procedure milestones. UChicago physicians performed the first two heart-kidney-pancreas transplants in Illinois (1995 and 1998), four heart-liver-kidney transplants (1999, 2001, 2003, and 2011) and hundreds of kidney-pancreas procedures.

Alignment for the future

Amidst this kind of history, it’s not surprising that UChicago was uniquely prepared to pull off consecutive triple-organ transplants. Preparations for both procedures began months earlier. Nir Uriel, MD, director of heart failure, transplant and mechanical circulatory support at UChicago Medicine, who managed the medical care for the patients, began to assemble the surgeons, nurses and anesthesiologists to perform the transplants, plus the heart, liver and kidney specialists to care for them up to and after the procedures.

This unprecedented amount of coordination relied upon a unique organizational structure at UChicago that facilitates collaboration among transplant specialists of all stripes. At many medical centers, transplant expertise is housed within traditional academic departments, such as surgery and medicine, aligned with specific organ systems. In the fall of 2016, UChicago Medicine created the Transplant Institute to consolidate transplant surgeons and medical specialists within a single unit, recognizing the unique needs of transplant patients.

“The idea is that rather than embedding different elements of a transplant program within the Department of Surgery or Department of Medicine, you pull it together in a cohesive way,” said Jeffrey Matthews, MD, the Dallas B. Phemister Professor and chair of surgery. “It was a new idea for the University of Chicago, but a model that had existed and proven to be successful at places like the Cleveland Clinic.”

Cleveland Clinic also factored into the search for a leader for the new institute. At the time, Fung was the director of Cleveland Clinic’s transplant center. After earning a medical degree and PhD

in immunology from UChicago, he trained under Thomas Starzl, MD, PhD, “the father of modern transplantation,” at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. In Pittsburgh and Cleveland, Fung became a transplant pioneer in his own right, leading large-scale clinical trials, developing novel surgical techniques, refining organ donation procedures and publishing hundreds of research articles.

“After Dr. Starzl retired, John Fung was probably the most prominent liver transplant surgeon in the world,” Matthews said. “I was looking for somebody who would be the John Fung of the University

of Chicago, never occurring to me that he might actually be interested in coming back here.

“When I heard that he might, we immediately put all hands on deck to make it happen,” Matthews said.

“One of the novel things about coming here was the institution’s willingness to set up a different structure, which was to break apart from the traditional academic silos that have existed here for 100 years,” Fung said.

“In the traditional silos you would do transplant part time, but you would do other things that the department wanted you to also do part time. That sort of diluted your efforts,” he said. “So we wanted committed people who all shared the same vision of building transplant, full time.”

Expanding possibilities

For Fung, building the transplant program means more than just increasing the volume of patients. He wants to make these lifesaving procedures available to more patients by expanding the possibilities, not only for how to perform organ transplants, but for who is eligible to receive them.

This means considering “high-risk” patients who would not otherwise get a transplant in the past. For example, Fung is an advocate for offering liver transplants to patients with acute alcoholic hepatitis. The standard practice has been to wait for these patients to have six months of sobriety before they can be added to the waiting list for a liver, for fear that they would relapse after transplant and ruin the new organ. But a landmark study published in The New England Journal of Medicine in 2011 shows that a subset of patients with no prior risk of liver disease and supportive social networks to help them remain sober after transplant can be successful candidates.

UChicago Medicine recently revised its sobriety policies to consider more of these patients. Their care is made possible by the multidisciplinary services of the Transplantation Institute, as liver experts, social workers and psychologists examine the patient’s psychiatric history, social support systems and likelihood to relapse after the life-threatening scare of drinking to the point of liver failure. The same teams help coordinate complex follow-up transplant care and counseling to maintain sobriety after surgery as well.

Fung also wants to offer liver transplants to more patients with such cancers as cholangiocarcinoma or neuro-endocrine tumors who might have been turned away in the past for fear that their cancer would recur. Fung believes these patients can be good candidates for transplant because new cancer drugs are more effective than ever, even if the patient relapses after transplant. Likewise, Uriel has been an early advocate for providing heart transplants for HIV-positive patients with heart failure now that antiretroviral drugs can effectively manage HIV/AIDS.

Fung envisions a day when UChicago Medicine looks beyond the standard heart, lung, liver, pancreas and kidney procedures as well. He helped launch an intestinal transplant program at Cleveland Clinic and would like to start one in Chicago. He also wants to explore composite tissue transplants, such as the face, hand or uterus. These are the kinds of procedures that spark the imagination about what is possible in medical science, even at an institution that routinely makes significant breakthroughs. But to Fung, that’s the entirely the point.

“We can’t compete with the larger health systems in the area by sitting back and relying on a huge network of patients coming to us. We don’t have that luxury,” he said. “To me, the way that you build a program is to distinguish yourself, create a niche for yourself and have people come here for that reason.

“The results are pretty good across the city for the standard criteria cases. If we stuck to that, we would just be a competitor. I don’t want to do that. I want to offer something different,” Fung said.

Medical breakthroughs and new technology have also made it possible to use more donor organs that wouldn’t have been available in the past. Organs from hepatitis C-positive donors were typically rejected by most transplant teams in all but the most desperate of cases, due to concerns over the infection causing post-transplant organ loss. But a few select centers, including UChicago Medicine, have reconsidered that philosophy in light of new antiviral medications that effectively cure hepatitis C.

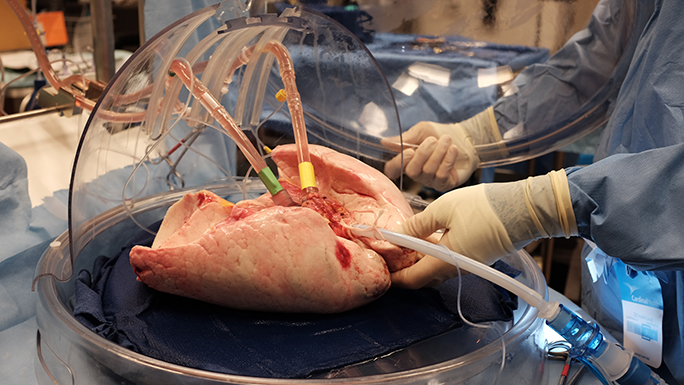

UChicago Medicine is also one of the first transplant centers in the U.S. to use a system called ex vivo lung perfusion (EVLP) to prepare donor lungs for transplant. Lungs are the most difficult organ to transplant because they are highly susceptible to infections in the late stages of the donor’s life. They can sustain damage during the process of recovering them from the donor or collapse after surgeons begin to ventilate them after transplant.

Because of these challenges, only one out of five donors who give organs of any kind provide suitable lungs for transplant. EVLP is a process that expands the pool of lungs that can be transplanted by evaluating the viability of lungs that may not meet standard criteria for donation. The lungs are placed in a machine that circulates solution through them to establish normal tissue flow and gently reinflates them in a controlled manner. More than 50 percent of lungs evaluated with the system can be used for transplant, significantly increasing the number of patients who can get a transplant.

Further out on the horizon, research that could restore or even rebuild a failing kidney is underway at the kidney and pancreas transplantation program.

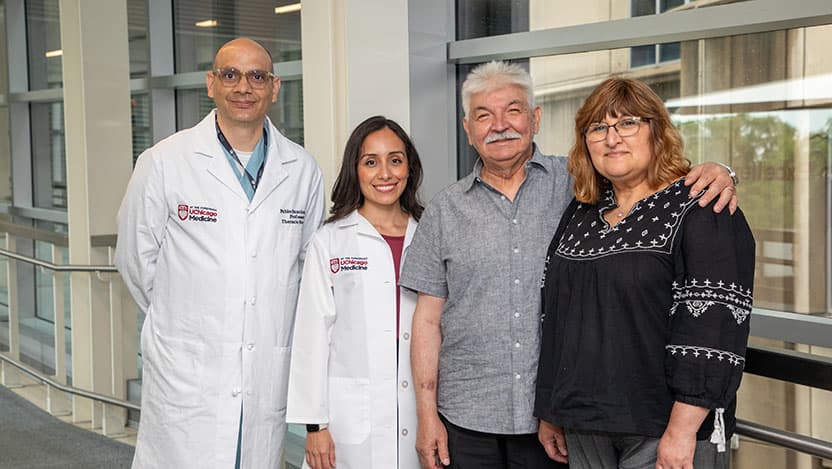

Becker, who performed the kidney transplants for McPharlin and Smith, has also served as president of the United Network for Organ Sharing (OPTN/UNOS) board of directors, a division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services that develops national organ transplantation policy. She has seen the UChicago Medicine transplantation program evolve over the years since joining the faculty in 2010.

“We have had the pieces in place to do multi-organ transplants for a long time, but we’ve had different strengths at different times,” she said. “Now it has all come together at the same time, and we’re in a very good position to do some very new and innovative things.”

The University of Chicago Medicine may never again perform multiple triple-organ transplants within the same year, let alone in less than two days. It was a stroke of luck that McPharlin and Smith were both on the waiting list in Chicago, that they both needed the same combination of organs and that they both found matching donors on consecutive days in December. But it certainly wasn’t luck that UChicago Medicine was prepared to save them.

“It’s a good feeling to be able to get to yes,” Becker said. “And I think that for complex medical and surgical procedures — in all disciplines, quite frankly — UChicago Medicine is a place where people work very hard to get to yes for the patient.”

Leaders in Organ Transplantation

Our transplant surgeons are among the best in the world. They have conducted thousands of procedures, earning national and international recognition for their expertise and research.

Learn more about our transplant team