Searching for links between IBD and mental health, through the gut microbiome

People with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) suffer from high rates of depression and anxiety. As many as 40% of IBD patients are diagnosed with depression during their lives, and up to 30% with anxiety.

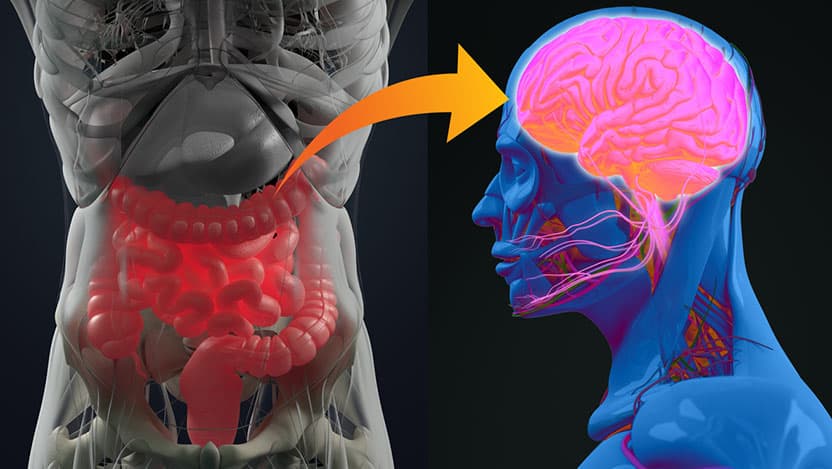

Living with any chronic condition is difficult, but IBD—which includes Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis—can be socially isolating, too. Patients may feel embarrassed by frequent trips to the bathroom or worried about how food and activity might trigger flareups. Add the pain, discomfort and fatigue caused by gastrointestinal symptoms, and it may seem natural that depression and anxiety follow for people coping with IBD. But new research on the connection between the brain and gut health, potentially mediated by the gut microbiome, suggests that mental health and IBD may be a two-way street.

The 'leaky' chain of events

When bacteria in the intestines help digest food, they produce and consume metabolites—amino acids, lipids, carbohydrates, and other nutrients the body needs. IBD and depression have a higher diversity of bacterial species, and people with IBD and anxiety have decreased diversity. This in turn affects the levels of metabolites these bacteria produce, affecting downstream processes like the immune system and nutrient uptake.

One of these metabolites, tryptophan, is often studied in relation to the brain because it’s a precursor to two well-known chemicals that affect mood and sleep: serotonin and melatonin. Tryptophan is an amino acid that comes from food (yes, including Thanksgiving turkey, although it’s more abundant in milk and tuna). It gets converted by gut microbes into other metabolites, some of which are transported to the brain to be converted into neurotransmitters. Studies show that David T. Rubin, MD, Joseph B. Kirsner Professor of Medicine and Chief of the Section of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition at the University of Chicago, thinks ultimately leads to a higher prevalence of anxiety and depression in IBD patients.

If we can explain that anxiety and depression in IBD are biological, it would revolutionize our understanding of these co-existing conditions.

“There’s a long history of people thinking IBD is psychosomatic, or that it’s caused by a certain personality type,” he said. “When in fact, it is likely related to genetic susceptibility, environmental triggers that result in changes in the microbiome, and a leaky blood-brain barrier. We believe that in most patients, the link may have a biological explanation, and not be simplified as behavioral or reactive to the stress of having IBD.”

A unique position to tackle both issues

The University of Chicago is uniquely positioned to perform this complex research. In addition to the large and well-known Center of Excellence for the care of people with IBD, the other facilities and talented scientists provide the perfect resources to tackle these complex problems.

Rubin and Ashley Sidebottom, PhD, Director of the Host-Microbe Metabolomics Facility (HMMF) at the Duchossois Family Institute at UChicago, had previously received funding from a donor to start this work. As a result of that investment, they also recently received $100,000 in pilot funding from the Gastrointestinal Research Foundation to further investigate the links between tryptophan metabolism, IBD, and anxiety and depression. The HMMF is a platform that helps researchers measure, characterize, and identify the metabolites produced or modified by gut microbes. The facility is housed on the UChicago campus and staffed by specialists who process samples and bioinformaticians who provide data analysis.

The team is also working on a new technique to collect blood samples from IBD patients in the clinic, requiring only a small drop of blood from a finger stick that is then analyzed for metabolites and biomarkers of inflammation. These data would then be correlated with measures of anxiety and depression, gathered either through questionnaires or a computer-based screening tool like that developed by UChicago public health researcher Robert Gibbons, PhD, and previously used in the IBD clinics here.

The hope is that they can find more evidence that mental health disorders in some IBD patients are related to inflammation and the microbiome of the gut, not simply the social and emotional effects of having a chronic bowel condition. Then, treatment of mood disorders in these people could become just as much about addressing the state of the bowel inflammation as it is about traditional therapy and antidepressant medications. In the same manner, they hypothesize that treatment of the mood disorders may down-regulate the inflammation of the bowel.

“We may have discovered a way to address these challenging problems that co-exist,” Rubin said. “If we can explain that anxiety and depression in IBD are biological, it would revolutionize our understanding of these co-existing conditions, provide new ways to predict or screen for them, destigmatize the mood disorders, and help us to markedly improve the quality of life of these individuals.”

David T. Rubin, MD

Dr. Rubin specializes in the treatment of digestive diseases. His expertise includes inflammatory bowel diseases (Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis) and high-risk cancer syndromes.

See Dr. Rubin's physician bio