A young Bronzeville woman's 120-pound weight loss leads to a successful kidney transplant

When doctors tell patients they must lose weight in order to have a kidney transplant, most people don’t do it.

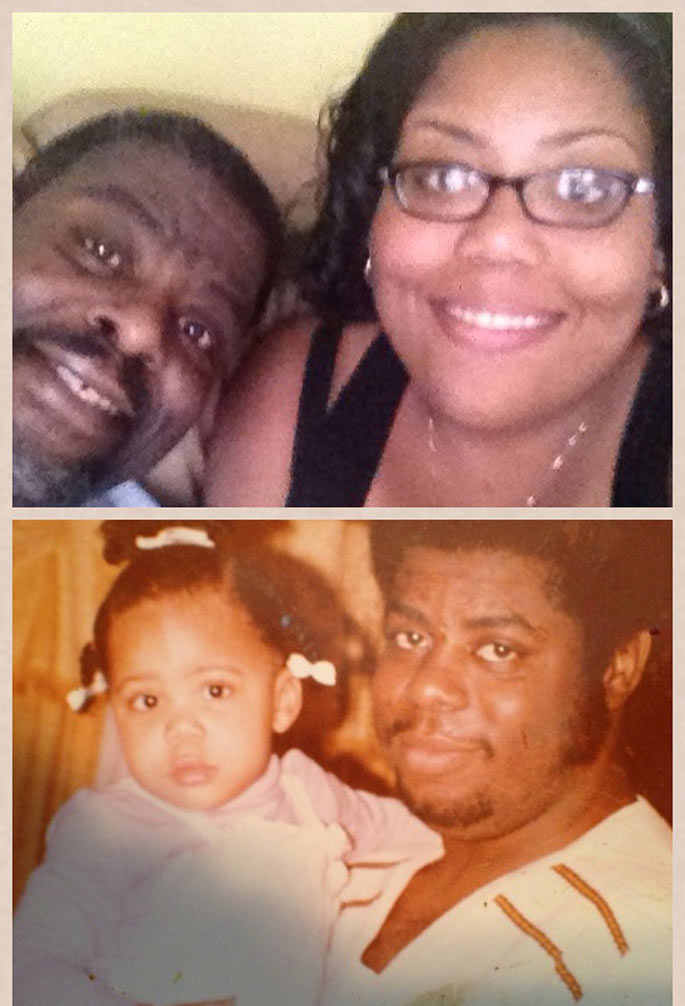

Quin Taylor wasn’t going to, at first. The Bronzeville resident was morbidly obese and despondent that her kidney failure was preventing her from finishing a master’s degree in psychology. At the same time, she was seeing her father struggle with kidney disease. The kidney transplant he had a decade earlier — after 18 years on dialysis — was starting to fail.

“I saw what my dad had been through,” she said. “But after two years of dealing with this, I decided I have to do it. I have to get out of this chair and get my life started. I had to lose the weight so I could have the transplant.”

Obesity and kidney transplantation

Obesity increases the risks of complications for a kidney transplant, including rejection. That’s why doctors generally require a patient to have a BMI below 42 before they will list them for a donor kidney. Taylor’s BMI was almost 60.

Her first step was to join Fitness Formula Clubs, a health club chain that would later be part of a groundbreaking UChicago Medicine study on helping kidney dialysis patients shed pounds to be eligible for a transplant.

Weight loss and the kidney transplant waitlist

Taylor began workouts with one of the club’s personal trainers, who cheered her on while a UChicago Medicine dietitian helped her revamp her eating habits. Slowly and steadily, Taylor, who is 5 feet, 11 inches tall, lost 120 pounds. After a year, when her doctors saw her progress and commitment — her BMI had dropped to 43 — they put her on a transplant waitlist. She had a successful kidney transplant in 2015, which was not only life-saving but life-changing.

Obesity increases the risks of complications for a kidney transplant, including rejection.

With support and long-term care from UChicago Medicine’s kidney transplant program, Taylor now lives a full life, maintains a healthy weight and runs her own consulting business, Tayloring Gratitude, which helps people facing chronic illness find gratitude, cope with reality and manage their lives and illness(es).

“I have so much respect for Quin,” said her kidney transplant surgeon, Yolanda Becker, MD, Director of the Kidney and Pancreas Transplant Program. “She could have easily said ‘I can’t. It’s too hard.’ Because it is so hard to lose weight and eat right! Most patients won’t do it. But she stayed positive and did it. This is an ‘I can’ story.’”

Taylor was a 20-year-old sophomore at Iowa State University when her kidneys first started to fail. Bloated, fatigued and needing to urinate every 20 minutes, she came home from school and saw her doctor at UChicago Medicine.

“They called me with my test results, and they said, ‘Ms. Taylor, you need to go to the emergency room … now,’” she said.

Diagnosed with kidney failure

Taylor was later diagnosed with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), a type of kidney failure. UChicago Medicine nephrologist Mary Hammes, MD, sustained Taylor’s kidney function for the next several years with medications. When they stopped being effective, she spent five years on kidney dialysis.

It was time for Taylor to decide: Did she want a kidney transplant? And if so, could she lose more than 100 pounds in order to have the surgery?

She made the decision to fight the disease, and take her life back.

It took a while to find her a donor, in part due to her less-common B+ blood type. On Nov. 4, 2015, she recalls feeling sad and starting to lose faith that a donor would be found. Before she went to bed, she said a prayer to God in which she turned over all her cares and worries to Him, because she’d done all she could do. The next morning, the phone rang at 3 a.m. It was UChicago Medicine transplant team. They’d found a kidney for her. She had the successful transplant surgery later that day.

A successful kidney transplant surgery and recovery

“After the surgery, I opened my eyes in the ICU, and I saw the world again for the first time in a long time. Everything was brighter. The colors were more vibrant. Like I woke up from a long sleep. I just kept thinking: ‘You’re going to live again,’” she said.

Today, five years since her kidney transplant, Taylor is thriving and healthy. She is diligent about regular follow-up appointments, and members of her UChicago Medicine care team have become her friends. They were especially supportive after her father, Eddie Taylor, died of kidney failure six weeks after her transplant. He’d been a UChicago Medicine kidney patient for 30 years — one of its longest-term kidney patients.

After the surgery, I opened my eyes in the ICU, and I saw the world again for the first time in a long time. Everything was brighter.

“What makes UChicago Medicine’s transplant program so special is that they care about you beyond just your health. During that tough time after my dad died, they were there for me. They made sure I was healthy in spite of everything that was going on around me,” she said. “If I ever need anything, I know that I can reach out to a member of the team and they will graciously help. Not because they have to, but because that’s simply who they are.”

Taylor, now 38, said her transplant not only gave her a second chance at life, but also an ingrained feeling of hope and gratitude. She often thinks about the person who lost their life and made the selfless decision to donate their kidneys.

“I’d be taking their life in vain if I didn’t keep on living and taking care of myself to use this priceless, priceless, priceless gift,” she said. “I am so forever grateful to them.”

Throughout her journey, Taylor has helped others, said UChicago Medicine transplant nephrologist Michelle Josephson, MD, Medical Director of the Kidney and Pancreas Transplant Program.

Empowering other kidney disease patients

“I will always be grateful to Quin for the time she spent volunteering to work on an international project, on which she spoke of improving the quality of life for transplant recipients, helping to empower and giving a voice to others with kidney disease,” Josephson said.

Black patients are at a greater risk of kidney failure because they have higher rates of type 2 diabetes, obesity, and genetic kidney failures — all factors that make a kidney transplant riskier, Becker said. Taylor’s case is proof that if you make a lifestyle change, you can have a kidney transplant with a positive outcome.

“Hopefully, her story will move someone to say, ‘I can do this, too,’” Becker said.

Kidney Transplant Program

UChicago Medicine's Kidney Transplant Program is dedicated to offering the highest level of care. We continue to improve transplant medicine through our research, providing patients access to the newest therapies and treatments.

Learn more about the kidney transplant programWhat you should know about living kidney donation

Our kidney transplant surgeon answers FAQs about living kidney donation.

Read the full article