Analysis of firearm-related suicide data reveals elevated risk in younger teens and in states with lax firearm laws

A Nathaniel Glasser, MD, a medicine-pediatrics physician at UChicago Medicine. “Our approach allows us to rid ourselves of certain mental heuristics that could otherwise lead researchers to possibly misattribute risk exclusively to populations that are more stereotypically associated with firearm violence.”

The researchers examined comprehensive CDC data and compared firearm suicide trends between two time periods: 1999-2014, when suicide rates were relatively stable, and 2015-2021, when rates increased. Despite the overall increase, they found that age-related trends remained consistent between the two time periods.

“This remarkable stability suggests that there are factors related to human development or age-related life circumstances that impact suicide rates,” said senior author Elizabeth Tung, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine at UChicago Medicine.

However, the researchers highlighted one notable exception to the observed stability in trends: firearm suicide risk in adolescents had accelerated and shifted younger, with an alarming increase in risk among younger adolescents aged 14-16 years.

“This observation represented a fundamental shift in the life course,” said Glasser, who was the paper’s lead author. “Unfortunately, this is consistent with other data suggesting an increasing crisis of mental health issues among younger teens.”

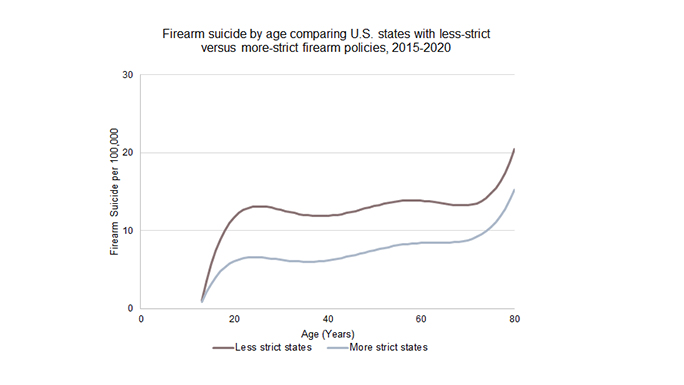

In addition to observing life course trends, the researchers compared firearm suicide rates between states with more strict and less strict firearm laws as measured by the Giffords Gun Law Scorecard. They found that stricter firearm laws were associated with 4.62 fewer firearm suicides per 100,000 annually, while there were no significant differences in non-firearm suicides.

“Our data make it staggeringly clear that policy environment does matter,” said Tung.

Putting their findings into context, the authors wrote: “The difference in suicide rates between states with less- versus more-strict firearm policy environments was nearly as large as the nation’s overall [firearm] homicide rate during the same period.”

Glasser and his collaborators hope this paper serves as a starting point for further research and future action. “Clinicians need to be attentive to life course risk and geographic variation, and researchers should begin doing more studies about effective, non-stigmatizing clinical interventions to prevent firearm suicide,” he said.

Tung said the immediate takeaway for primary care providers like herself and Glasser is to have conversations with their pediatric and adult patients about firearm safety when opportunities arise.

She shared an anecdote that recently hit home for her: “I recently spoke with a patient who had just lost a family member to suicide. They were having a tough time and were concerned for their own safety, so as we were discussing risk factors, I asked if they had a gun at home. The patient was a little surprised and said, ‘I flushed all the pills down the toilet, but I didn't even think about the gun.’”

“People sometimes have weapons tucked away in their closet and don't even think about it as a risk factor for themselves,” Tung said. “In the context of our research, the interaction reaffirmed to me that we should be asking about firearms, especially when there are mental health risks.”

The study, “Age Trends and State Disparities in Firearm-Related Suicide in the US, 1999–2020,” was published in Health Affairs in November 2023. Co-authors include Nathaniel J. Glasser, Nabil Abou Baker, Harold A. Pollack, Sohail S. Hussaini, and Elizabeth L. Tung.