Babies with hydrocephalus caused by toxoplasmosis have good outcomes with prompt treatment

Babies born with toxoplasmosis, which is caused by a congenital parasitic infection, can develop hydrocephalus, a condition where excess fluid creates damaging pressure in the brain.

A new study led by University of Chicago Medicine researchers, collaborating with a group of physician scientists in Chicago, suggests that the faster a baby with congenital toxoplasmosis can be given a fluid-draining shunt to treat their hydrocephalus – even in cases of severe hydrocephalus – the better their cognitive outcome.

Based on a longitudinal study of 65 patients born with Toxoplasma gondii infections who developed hydrocephalus during a 38 year period, the research, published in the Rima McLeod, MD, lead author of the study and a professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences and pediatric infectious diseases who directs the Toxoplasmosis Center at UChicago. “An infection early in pregnancy can lead to severe disease in the baby, and even with milder involvement at birth, virtually all of these untreated children end up having eye disease by the time they are teenagers and some may experience a fall-off in cognition as well.”

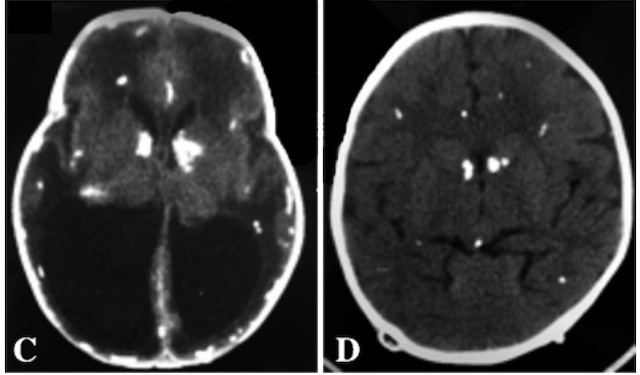

Babies born with toxoplasmosis can develop hydrocephalus, when cerebrospinal fluid that normally circulates through the brain’s ventricles backs up and damages the brain. To treat this, surgeons place a tube called a shunt in these children so that the excess fluid in the ventricles can drain to the abdomen.

Little has been known about the effectiveness of this treatment on the long-term neurological function of these patients, however. Furthermore, shunt surgery for children with severe, presumed irreparable brain damage from toxoplasmosis-linked hydrocephalus at birth was in the past deemed unlikely to be beneficial.

Quick treatment, better outcomes

Of the 46 patients who underwent shunt placement, almost all showed improvement following placement. Four patients showed no improvement, one patient died and one was lost to follow up. Dramatic increases in thickness of the cortical mantle, the outer gray matter of the brain, were not uncommon. Importantly, there were patients who presented with severe hydrocephalus and cortical mantle thinning who, after shunt placement, experienced an impressive cortical re-expansion and ultimately normal cognitive function.

The researchers found that the longer it took to surgically intervene with a shunt after diagnosing hydrocephalus, the worse the outcome. In the 28 patients for whom data was available, delayed shunt placement of 25 or more days after a diagnosis of hydrocephalus was associated with lower IQ scores compared to patients who underwent shunt placements less than 25 days after diagnosis. For the 31 patients for whom motor data was available, gross motor skills trended toward worse as time to intervention increased, although it did not achieve statistical significance.

“Although there were a range of outcomes for these children, shunt placement combined with medical treatment gave these children a chance to live full, normal lives,” said William Cohen, a UChicago student who helped with study data analysis.

The researchers are now seeking FDA-approval for a rapid, point-of-care (POC) diagnostic test that can be administered during pregnancy. The POC test quickly analyzes blood from a finger-prick to determine whether a woman has been infected with Toxoplasma gondii during pregnancy, meaning treatment can be initiated more quickly for improved outcomes.

The study, "Outcomes of hydrocephalus secondary to congenital toxoplasmosis," was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the Mann Cornwell family, the Engel family and “Taking out Toxo,” the Morel family, the Pritzker family, and the Rooney-Alden family.

Additional authors on the study include David McLone, Charles Swisher and Gwendolyn Noble of Northwestern University; Richard Penn of the University of Illinois at Chicago; Peter Heydemann and Kenneth Boyer of Rush University Medical Center; Peter Rabiah of NorthShore University Health System; and Shawn Withers, Samuel Hutson, Kelsey Wheeler, Kristen Wroblewski, Theodore Karrison and Joseph Lykins of the University of Chicago.