The life and times of a trailblazing physician-scientist

In 1970, there was no treatment for the blood disorder sickle cell anemia, and knowledge of how to manage it was rudimentary. For patients, life expectancy was about 20 years. Roughly one in 500 African Americans was born with the condition, noted an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association that October. Yet funding was a fraction of that for less prevalent disorders afflicting other groups, the author wrote.

On the streets, the Black Panther Party took matters into its own hands, utilizing a newly available testing kit to mobilize screening in African American communities, including in Chicago.

In February 1971, President Richard Nixon designated sickle cell anemia one of two critical areas for urgent investment under his proposed “National Health Strategy.” The other was cancer. The following year, he signed the National Sickle Cell Anemia Control Act, which authorized funding for screening, outreach and research to “reverse the record of neglect on this dread disease.”

After decades of inaction, there was a headlong rush to tackle sickle cell anemia. And in the well-intentioned zeal to roll out mass testing and raise awareness, little attention was being paid to the accuracy of information disseminated to the public and the ethical implications of screening on the scale that was being embraced, said an outspoken professor of medicine and pathology from the University of Chicago.

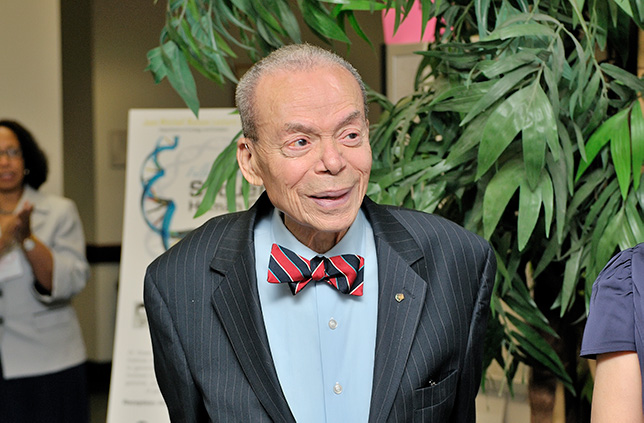

James E. Bowman, MD, who died in September 2011 at 88, had just become the first tenured African American faculty member in medicine at the University.

In journal articles and meetings with lead players, Bowman excoriated the conflation of sickle cell anemia with the more common sickle cell trait (in which just one predisposing gene, as opposed to the two needed to produce the disease, is present, and the person is healthy) that was fanning public alarm. Recently named director of the University’s laboratories, he assailed crude testing practices. To improve understanding of test results, he called for more education and counseling.

Clarice D. Reid, MD, former director of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Sickle Cell Disease Program, can still recall “the shock effect” of his words.

“Jim spoke out. It wasn’t just about doing the right thing; you had to do it the right way.

“Sickle cell was launched as a policy issue with no information about it in the general populace,” Reid added. “Coming out of the civil rights movement, there was mistrust and unrest in the black community, and now there's this disease. There was widespread hysteria and confusion between sickle cell disease and sickle cell trait. On top of that, we're trying to mount a national program."

In Oakland, California, birthplace of the Panthers, Bertram H. Lubin, MD, was then co-director of the Northern California Comprehensive Sickle Cell Center. “I thought, ‘This is nice, a community group doing screening,’” he recounted. “But there was no informed consent, and people who tested positive didn’t know if they had disease or trait. Jim was furious. He thought the intentions were good, but the implementation was outrageous. And he wasn’t shy about saying so."

Bowman didn’t confine his scrutiny to grassroots efforts. He castigated the government for propagating misinformation, and questioned the wisdom of aggressive screening programs underway in several states, cataloging instances of “genetic discrimination.” These included hiking insurance premiums for people with sickle cell trait and dismissing black flight attendants with it, based on the misunderstanding they were unable to work at high altitude.

“At the time, we were seeking to screen the whole world,” Reid said. “Jim reminded us there were potential ethical issues and the right not to know your genetic status.”

It was a critique that had all the more impact for the person making it: a deeply engaged researcher committed to addressing the very issues they were raising.

From 1973 through 1984, Bowman presided over the Comprehensive Sickle Cell Center at the University of Chicago, one of 10 such centers nationwide dedicated to patient care, research and education.

Funded by the National Institutes of Health, a major educational publication from this center was “Sickle Cell Fundamentals,” the 1975 book he wrote with colleague Eugene Goldwasser, PhD, that became required reading by government-funded programs. Between 1972 and 1975, Bowman also served on six national committees concerned with sickle cell-related matters. He also helped organize a landmark sickle cell exhibition at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago.

While there remains much to do, today sickle cell patients can live five decades and longer, thanks to improved knowledge of the condition and how to manage it.

Bowman's contributions reverberated beyond sickle cell. Olufunmilayo Olopade, MD, Walter L. Palmer Distinguished Service Professor of Medicine and Human Genetics and Director of the University of Chicago Medicine’s Center for Clinical Cancer Genetics and Global Health, credits Bowman with “informing” her advocacy for patient protection protocols adopted in hereditary cancer screening.

And in the heady early days of genomics in the mid-1990s, Bowman, by then a senior scholar at the University of Chicago’s MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics, was recruited to the Ethical, Legal and Social Issues Working Group of the Human Genome Project. Amid “reports of a gene for this or that condition,” the air was thick with “genetic determinism,” recalled chair Troy Duster, PhD, Chancellor's Professor of Sociology at the University of California, Berkeley.

“Jim was the most vociferous voice. I used to tell my social science colleagues that on bioethics issues he was a better social scientist than some of them, because they didn’t know a lot about the scientific aspects of disease, and tended to rely on published literature or physician colleagues. Jim understood the medical part, but was also sophisticated about the social and political underpinnings of medical decisions.”

Pioneer in the emerging field of genetics

Such insights were grounded in Bowman’s experience as an early geneticist confronting the ethical quandaries of genetic testing before the emergence of bioethics as a stand-alone discipline, and as an African American physician-scientist confronting prejudice in segregation-era America.

The eldest of five, Bowman was born in 1923 in then-segregated Washington, D.C. Bucking his father’s wish that he follow him into dentistry, Bowman enrolled at Howard University College of Medicine. He completed his studies in three years (as part of an Army-sponsored expedited curriculum) in 1946, earning induction into the Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society as a leading member of his graduating class.

Precluded by segregation from joining the Army as an officer, he completed an internship at Howard’s Freedmen’s Hospital before moving to Chicago, where in 1947 he secured a residency in pathology at St. Luke’s Hospital. Bowman was the first black resident. In a 2006 interview for the UCLA-Johns Hopkins Oral History of Human Genetics Project, he recounted that a friend told him: "But you know you have to go in through the back door." Recalled Bowman, "Well, I said, ‘That’s absolute nonsense. If I’m a resident, I’m going to walk through the front door.’" He did, as a group African American hospital employees watched. The next day, he recalled, they walked through the front door with him.

After the residency, Bowman became pathology chief at Provident Hospital until 1953 when, amid the Korean War, he was drafted, opting to join the Army’s Medical Nutrition Laboratory in Denver, Colorado, as pathology chief. He’d recently married Barbara Taylor (daughter of the first African American Chicago Housing Authority chief, Robert Rochon Taylor), who had completed a master’s degree in education at the University of Chicago. When the couple moved to Denver, Barbara taught at Colorado Women’s College.

When his service ended in 1955, neither he nor Barbara could stomach “anything that smacked of segregation,” Bowman recounted in the oral history. They decided to look for positions overseas. They decamped to Nemazee Hospital in Shiraz, Iran, where Bowman became chair of pathology. Barbara taught preschool and lectured in psychology and anthropology at the hospital-affiliated medical school.

“It completely changed the trajectory of his career,” said his daughter, Valerie Bowman Jarrett, a Distinguished Senior Fellow at the University of Chicago and Senior Advisor to the Obama Foundation.

From this unlikely setting, Bowman bootstrapped himself into the forefront of the emerging field of genetics.

It all began with a fateful encounter with a gravely ill little girl.

Miraculously, following a blood transfusion, the child recovered. Bowman and his colleagues were mystified, he recalled in the 2006 interview. But a visit by Bowman to a market where he spotted fava beans provided the breakthrough. They were dealing with favism, a genetic condition in which consuming fava beans triggers a dangerous anemic reaction.

Bowman led expeditions to collect blood samples from among Iran’s ethnic groups to understand susceptibility to favism across different populations. The fieldwork offered a fascinating glimpse into different cultures, the genetic footprints of their movement and the evolutionary dynamics shaping genetics.

Bowman immersed himself in the literature. “I taught myself,” he said in the oral history. “It was partly biochemical genetics, anthropology, history. . . It was wonderful.”

He struck up correspondences with researchers worldwide, including Alf Alving, MD, who was at the University of Chicago, where researchers had linked the same genetic mutation involved in favism to a potentially fatal reaction to the antimalarial primaquine. Alving invited Bowman to look him up should he return to America.

It was a formative time on the personal front, too, said Jarrett, born in Iran in 1956. “It strengthened my parents’ relationship because they were so far from home and had to rely on each other. They also made lifelong friends they treasured deeply.”

In 1960, they left Iran for the University of London, where Bowman had won a fellowship at the Galton Institute, a pioneering training ground for geneticists. Here, he would finally “learn the genetics that I’d been reading about,” he said in the 2006 interview.

Returning to America in 1961, he took up Alving’s offer. Bowman subsequently was offered a dual appointment as assistant professor of medicine and pathology, and director of the University’s blood bank. “A new era of genetic enlightenment occurred in the 1950s,” said Alvin Tarlov, MD, former chair of the Department of Medicine at the University of Chicago. “Jim was the expert on the clinical meaning of genetic disorders that affected red blood cells."

Bowman’s field studies in population genetics took him to Mexico, Ghana, Nigeria, Ethiopia and Uganda. From 1959 to 1967, he published eight papers in Nature, six as lead author. A summation of much of his research, “Genetic Variation and Disorders in Peoples of African Origin,” came out in 1990.

Legacy of intellectual curiosity and mentorship

But Bowman was never too busy to extend a helping hand to students.

From 1986 to 1990, this mentoring was done in his capacity as Assistant Dean of Students for Minority Affairs for the Pritzker School of Medicine. “It was supposed to be a 20% commitment, but some days it took 100% of the time. He didn’t compartmentalize,” recalled colleague Rosita Ragin, former Assistant Dean for Multicultural and Student Affairs.

“He’d had a tough time himself and was bound and determined to make it easier for the next generation,” said Jarrett. “His office door was always open.”

That door happened to be next to Pritzker’s main lecture hall. And it streamed a procession of students, many now leaders at the University.

For Anita Blanchard, MD, Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Chicago Medicine, the first member of her family to attend medical school, Bowman was a “lifeline.”

“He became like a second father,” she said. “My father was wonderful, but he couldn’t help with navigating medical school and a career as a physician. Dr. Bowman stepped in and did that.”

Jarrett remembers a home in which public service was paramount — Barbara Bowman co-founded the Erikson Institute, a pioneer in early education — and expansive discussions reflected her father’s “insatiable intellectual curiosity.”

“The conversation around our dining room table was always a spirited conversation. It wasn’t for the faint-hearted; you had to come prepared to defend your positions.”

Bowman doted on Barbara, Valerie and granddaughter Laura Jarrett (a 2010 Harvard Law School graduate), whom he used to pick up daily from the University of Chicago Laboratory Schools.

“He made us his highest priority, no matter what else was going on in his life,” Jarrett said.

Many mentees were drawn into the close-knit Bowman household in Hyde Park and its extended social circle.

“Jim was not a parochial thinker,” said Raphael C. Lee, MD, ScD, the Paul S. and Allene T. Russell Professor of Surgery, and Professor in the Departments of Medicine and Organismal Biology and Anatomy. “He was very knowledgeable and thoughtful about extant matters of human health and rights around the world."

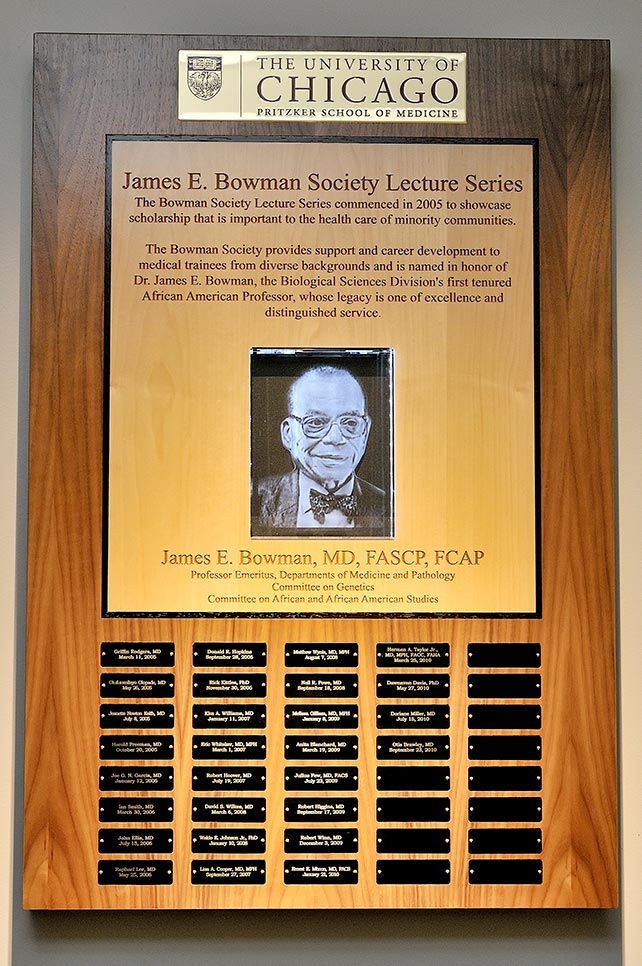

The Bowman Society seeks to honor Dr. Bowman's legacy by bringing the University community together to focus attention on scholarship that is important to the health care of minority communities and to provide support and career development to individuals at all levels of training in order to support multicultural diversity in the University's Biological Sciences Division. The society's lecture series began in 2005.

In 2008, Bowman’s health began to falter. He was diagnosed with cancer. He battled it gamely, but finally succumbed on September 28, 2011.

“I never met anyone with such boundless enthusiasm and deep-seated commitment,” Ragin said. “Yet he always seemed so modulated and paced.”

The spirit was intact to the end, she said. In the final days, Ragin visited his bedside. “I took his hand, and he grasped it firmly and raised it high. I said, ‘I know, Jimmy, we have a lot left to do. I’m on it.’ Without a word, he made the effort, exhorting me.”

Stephen Phillips is a freelance writer. This story appeared in