Resilient 'SuperAgers' show the positive side of growing old

Even though the two women had met only once or twice before, 110-year-old Edith Renfrow Smith lit up as soon as 84-year-old Sheila Nicholes entered the room.

“Here comes another SuperAger!” she exclaimed.

Nicholes laughed and gave Smith a hug. “I sure am a SuperAger!”

The joyful exchange was a snapshot of the camaraderie that in many ways lies at the heart of the SuperAging Research Initiative, which is centered at the University of Chicago’s Healthy Aging & Alzheimer’s Research Care (HAARC) Center.

What does it mean to be a SuperAger?

Led by Emily Rogalski, PhD, the Rosalind Franklin Professor of Neurology at UChicago, the program identifies and studies older adults who are aging remarkably well.

Specifically, Rogalski and her fellow researchers define “SuperAgers” as people over the age of 80 who have memory performance at least as good as average people in their 50s and 60s. In contrast to the more common approach of studying what goes wrong as people age in order to find solutions, the SuperAging Research Initiative focuses on discovering what can go right.

“People’s faces light up when we ask questions about what’s helping people live long and live well and they get to tell us about a friend, neighbor or relative who fits that positive description,” Rogalski said.

Study participants come to the HAARC Center to share their medical and family histories, discuss their daily habits and interests, and undergo detailed memory testing. Researchers also perform brain scans and collect blood samples to investigate genetic and other biomarkers of health. Outside the lab, wearable sensors offer more precise data about SuperAgers’ sleep, physical activity and even social interactions.

Once SuperAgers are part of the program, they’re in it “for life and beyond”: They return every two years for repeat assessments, and at the end of their remarkable lives, some donate their brains to let the neuroscientists get a closer, more detailed look at the cellular and molecular features that set them apart.

“I hope they find something in common between my brain and the other brains they’re studying, because my brain still seems to be able to connect so many things, and so many memories have not dropped off even as I age,” Smith said.

At 110, Smith is currently the oldest SuperAger in the program, while at a self-proclaimed “84 years young,” Nicholes is what many of the others jokingly call a “baby SuperAger.”

“Studying what is going well in SuperAgers has the potential to someday help those who suffer from some age-related conditions, so there’s also an element of giving back to the world,” Rogalski said.

Nicholes echoed the sentiment: “I jumped at the chance to get involved in the SuperAgers program because I know it’ll help. I’m interested in the brain and what it does and how you can keep it healthy. Being in the SuperAgers program helps me stay sharp, and what they learn in the study can help people later on, like my great-grandkids.”

Changing the narrative about aging

“I think it’s especially important to tell the public about Black SuperAgers and have us talk about what we’ve been doing to reach this age and feel how we feel,” Nicholes said. “That exposure can be helpful to other Black people who have questions about aging.”

Phyllis Timpo, MS, Director of Community Engagement, Outreach, and Recruitment at the HAARC Center, said that when she goes out and talks to people — especially within Black communities — they say they're tired of hearing about disparities and things going wrong with their health.

“SuperAging research gives us a chance to tell the stories of amazing people on the South Side and West Side of Chicago who are able to be resilient and live long, full lives full of cool stories despite all the social determinants of health,” Timpo said.

Smith and Nicholes are two of those amazing people. Smith has lived — and is still very much living — a rich and remarkable life, from being the first Black woman to graduate from Grinnell College to working on redlining research at UChicago and teaching in Chicago public schools. She drove a car until she was over 100 years old, and she still cooks, participates in her church and has an active social life.

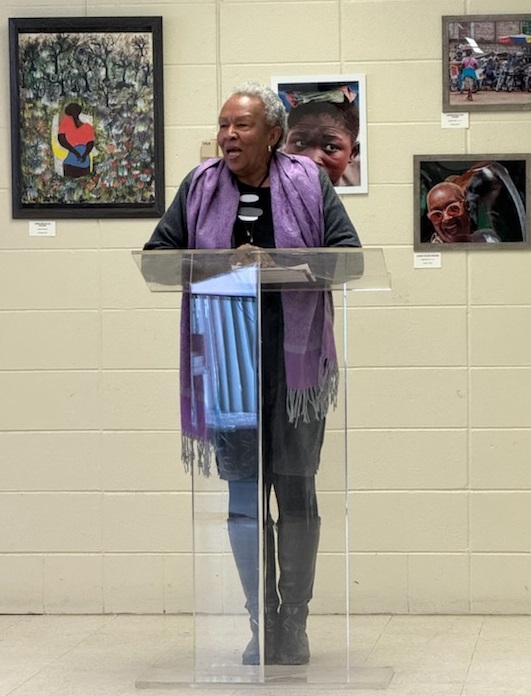

For her part, Nicholes embraces every opportunity to demonstrate just how active older adults can be. She still travels internationally, and she recently presented her photography and paintings at an art showcase co-organized by the SuperAging program and Africa International House, a HAARC Center community partner. The event allowed her to invite friends, family and neighbors to celebrate her artwork and talk about just how much she continues to accomplish at her age.

“I just think you have to stay active and keep doing things, and I’m enthusiastic about explaining that to my community,” Nicholes said. “Other communities, other races, talk about this more, but there’s still stigma among us that we have to overcome.”

Stories of resilience

In addition to remaining active and maintaining strong social connections, a common thread researchers have identified among the SuperAgers is resilience. Many haven’t had life handed to them on a silver platter — some were the only members of their families to survive the Holocaust; others lost children or spouses at a young age; others experienced poverty throughout their lives.

“It’s not that things have been easy, but they had a choice: They could bounce back and keep moving on, or they could let the challenges define them,” Rogalski said. “The majority of our SuperAgers show that resilience: they choose to talk about the positive side of things, or the ways they've gotten through hard times.”

Timpo concurred, adding: “Black SuperAgers are a living testament to the fact that it’s possible to keep going, maintain social connections and find joy despite living through so many societal events that negatively affected Black people.”

Making aging research accessible to minoritized communities

Having the SuperAging research located on the South Side of Chicago makes it easier for a diverse group of people from the community to join the program, which is crucial for making sure the findings are useful for as many people as possible.

“So many people — particularly Black older adults — grew up in this neighborhood and still live here and come to UChicago Medicine for their healthcare. Being embedded in the community builds trust and makes it easy for people to come participate,” Timpo said.

Nicholes called out the fact that many clinical research studies fail to include very many people who look like her.

“Many people from my culture don’t want to participate in research, but I participate in a program if I feel it’s really good and is non-invasive,” she said. “I trust this program, and I’m an advocate for other people joining it.”

Smith agreed. “It’s important that they include different groups in the study. If somebody can look at my brain and get some information that will help other people like me, then I absolutely want them to do that.”

Both Smith and Nicholes say they plan to participate in SuperAging research “for a very long time.”

To learn more about the SuperAging Research Initiative, visit the HAARC Center website.