Surgery helps young woman bounce back from rare brain condition

Jan. 25, 2018, began like most days for 16-year-old Olivia Parrillo. She woke up early, showered, ate breakfast and drove to Hinsdale Central High School, where she finished her homework before classes started. During lunch, however, everything changed.

“I reached out to grab a yogurt, and all of a sudden, something shot through my arm,” Parrillo said.

She collapsed into a seizure that lasted nearly five minutes. Fortunately, she was surrounded by friends and school staff who immediately sought help.

Parrillo was rushed to a local hospital, where her parents, Tracey and Mike, met her. At first, Tracey attributed the incident to stress and exhaustion since her daughter had just gone through a hectic weekend participating in a dance competition, and on top of that, had homework and tests.

“It seemed like the perfect storm,” Tracey said, “but it was a bigger storm than we anticipated.”

We were willing to travel to the ends of the earth to get the best care for Olivia. But lo and behold, the number one guy in the field was right here in our backyard.

Doctors informed the family that Parrillo had a cerebral cavernous malformation, or CCM, on her brain. An under-diagnosed condition, CCM affects more than 1 million Americans. The malformation consists of a cluster of dilated blood vessels that form bubble-like structures called caverns. Often compared to the shape of a raspberry, the blood-filled caverns can leak, causing seizures, headaches, bleeding in the brain, weakness and in some cases, even paralysis.

Parrillo didn’t experience any symptoms until her seizure.

A neurosurgeon at her local hospital recommended she take an anti-seizure medication for the rest of her life. He expressed concern that operating on her could cause facial paralysis since the CCM lesion was located in a part of the brain that controls facial movement.

Concerned by the prospect of their daughter being on medication for the rest of her life and worried that another seizure could cause more serious problems, including a stroke, Tracey and Mike contacted Mark Siegler, MD, their physician at the University of Chicago Medicine, for a second opinion. Siegler referred the family to internationally renowned neurosurgeon Issam Awad, MD, director of neurovascular surgery at UChicago Medicine. Awad and his team see more CCM patients than any other center in the world.

“We were willing to travel to the ends of the earth to get the best care for Olivia,” Tracey said. “But lo and behold, the number one guy in the field was right here in our backyard at our choice of hospitals.”

Awad is not only an expert in treating CCM, but he has also been researching the condition for nearly three decades. His work is supported by a combination of federal grants and private philanthropy.

“Every piece of knowledge we generate starts with an idea,” Awad said. “But before we can convince the federal government to fund us, we need to test our ideas via pilot studies. These studies, which help lay the foundation for the next breakthroughs, are entirely supported by philanthropy, most of which comes from grateful patients and families affected by these conditions.”

His current pilot projects include developing a blood test to predict which CCM lesions will bleed and developing new treatments to stabilize lesions that have bled to prevent them from bleeding again.

In recognition of their leadership and excellence in CCM research and care, UChicago Medicine was designated by the Angioma Alliance in 2016 as the first Clinical Center of Excellence for treatment and research into the disease.

“Cavernous malformations are relatively rare,” Awad said. “Even a neurosurgeon who specializes in vascular problems of the brain might not see more than five or so cases a year. Our team sees two to three a week.”

Five days after Parrillo’s seizure, the family met with Awad.

“It took him just a couple minutes to convince us that Olivia should have surgery,” Mike said. “He put us at ease and said, ‘She’s 16 years old; she should be at 100%.’”

Using innovative brain mapping technology, Awad and his team identified the specific location of the CCM lesion and determined the function of each part of the brain surrounding it.

“Our team has substantial experience operating on the area of the brain where Olivia’s lesion was located,” Awad said. “Although we were well aware of the region’s importance, we were confident that we could remove the lesion safely. We knew from our past research and experience that removing the lesion would give Olivia the best chance of being seizure-free.”

Parrillo came in for surgery four weeks later, once the swelling had gone down in her brain. Since Awad and his team knew exactly where the lesion was located, they were able to operate without shaving her head. Instead, one of Awad’s team members braided Parrillo’s hair so the lesion was easily accessible.

“We made every effort to not only safely and successfully treat Olivia, but to also minimize stress and anxiety as much as possible,” Awad said.

The surgery took about three hours. While Awad operated, a team of neurophysiologists mapped Parrillo’s brain activity, ensuring everything went smoothly.

Over the next couple of weeks, Parrillo recovered. Five weeks post-surgery, her parents reached out to ask if they should cancel a spring break trip they’d planned before their daughter’s seizure.

“Dr. Awad told us there was no need to cancel our trip,” Tracey said. “In fact, he said Olivia could go snorkeling!”

By late April 2018, Parrillo was cleared to dance again. She performed jazz and contemporary dance four consecutive nights as part of her dance studio’s annual showcase.

“It was amazing,” Tracey said. “She just had brain surgery, and there she was back on the stage. She had even learned all of the new choreography.”

In recognition of her impressive accomplishments, Parrillo won the “bounce back” award at her dance team’s end-of-season celebration.

Seven months post-surgery, an MRI showed her brain had fully healed, and an electroencephalogram (EEG) showed no further signs of seizure activity.

Recently, Parrillo stopped taking anti-seizure medication and started her senior year of high school. The only remaining sign of her surgery is a scar on her head hidden beneath her hair.

“It’s funny because sometimes my teachers will say, ‘Come on, this isn’t brain surgery,’ and I’m thinking, ‘I’ve been through that!’” she said.

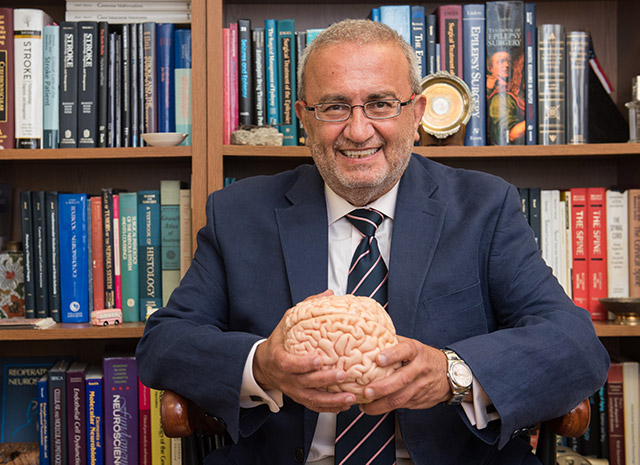

Issam Awad, MD

Issam A. Awad, MD, is an internationally recognized leader in neurosurgery. He is skilled in the surgical management of neurovascular conditions affecting the brain and spinal cord, including cerebral aneurysms, cerebrovascular malformations, carotid surgery, hemorrhagic stroke and skull base tumors.

Learn more about Dr. Awad