What you should know about the new mpox outbreak

Public health teams are learning more about the global mpox outbreak, which continues to gain momentum. As case counts rise — locally and across the country — it’s more important than ever that people understand how this virus is transmitted, what activities put people at risk and what to do if you think you’re infected or have been exposed.

This situation continues to evolve, and the information below is based on the understanding of this outbreak at the time of this post's publication. Much like we did with COVID-19, we’ll likely know much more in the weeks and months to come. But for now, here’s what we think you should know about mpox and how you can stay safe.

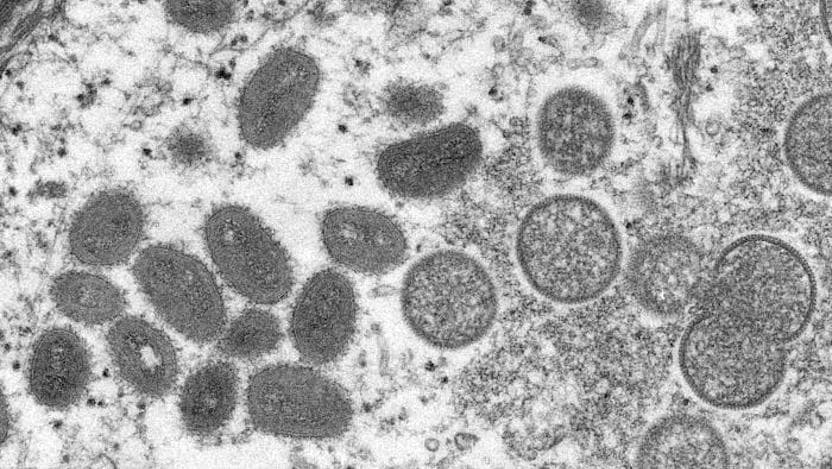

Q: What is mpox?

A: Mpox began in animals and was transmitted to humans. It’s transmitted through close contact with another mpox patient or from rodents carrying the disease. It’s part of the same family as other poxviruses including smallpox (orthopoxviridae), and was first discovered in humans in 1970.

Q: What does mpox look like?

A: An mpox rash starts as red spots and progresses over time to pus-filled, blister-like lesions. They remain infectious until they eventually scab over and fall off, which can take up to a month. The lesions are generally all the same size and develop at the same rate. These painful pustules are usually — but not always — found on the face, hands, legs and feet. Sometimes this rash is found only in or on the genitals or anus, which means symptoms may be mistaken for a sexually transmitted infection or STI.

A person with mpox may feel like they’re coming down with a cold or flu days before their rash develops. They may also have swollen lymph nodes.

Q: How does mpox spread?

A: Mpox spreads through direct, prolonged skin-to-skin contact with lesions or the fluid inside them. Risk of exposure through skin increases with time and friction.

In addition, the virus can be spread by breathing in or directly contacting infected respiratory droplets or other body secretions, like saliva. Mpox has also been transmitted from surfaces that were contaminated with respiratory droplets or fluid from the lesions, but that’s less likely to occur than infection from skin-to-skin contact.

Q: What activities are more likely to expose me to mpox?

A: Your risk escalates when your uncovered skin is in contact with an uncovered mpox lesion. That risk gets higher the more abrasion there is during the contact and the more time your skin touches the infected skin. Highest risk activities include sex, intimacy, and kissing. Other risky activities include living with someone who has mpox, sharing towels and sheets with an infected person, wrestling and attending raves, large concerts or circuit parties where lots of people are packed into close spaces.

Casual contact — like public transportation, grocery shopping or touching door handles or gym equipment — has a much lower, even negligible risk.

Q: How can I protect myself from mpox?

A: If you think you’re going to be in a crowded space where your skin may be exposed to someone else’s, wear more clothing and consider wearing a mask. If you’re having sexual or intimate contact with multiple people or with anonymous partners, consider modifying your sexual behavior — at least for now. Consider the risk of new or unknown partners and check your own skin and your partners’ skin for rashes or lesions. If you’re eligible to get an mpox vaccine — either because you are in a high-risk category or because you’ve been exposed — you should strongly consider it. (Be aware that supplies and eligibility are limited for now.)

While you’re unlikely to catch mpox from door handles or passing contact with someone who’s infected, we recommend people continue to follow common-sense infection prevention measures, such as wearing masks, washing hands regularly and cleaning high-touch surfaces.

Q: How long does it take to become sick?

A: It can take anywhere from five to 21 days to become sick with mpox after an exposure. That long incubation period means we can give people treatments or vaccines early after an exposure to keep them from getting sick.

Once someone becomes infected, their illness lasts about two to four weeks.

Q: What should I do if I’ve been exposed to mpox?

A: If you know you’ve had close contact with someone who has mpox, contact your healthcare provider or your local health department right away because you may be eligible to get a post-exposure vaccination. This is called post-exposure prophylaxis and may be help to keep you from getting infected.

These vaccines are limited so they are only reserved for people who’ve had high-risk exposure to someone with mpox.

Anyone who has had contact with mpox should plan to monitor symptoms for three weeks and get an mpox test if you begin to develop a rash or lesions.

Q: Can I get tested for mpox?

A: Mpox testing is widely available in the community and here at the University of Chicago Medicine. Unlike a COVID-19 test or a blood test, doctors can only test for mpox by scraping cells from a fluid-filled mpox lesion. Without a lesion or a rash, you won’t be able to get a mpox test.

If you have a lesion, you should request an appointment with a primary care provider, community clinic, infectious diseases specialist, dermatologist or a sexual wellness clinic, since these providers will have the most familiarity with mpox cases.

At your appointment, your health care provider will examine your skin and ask questions about your exposure risk and your health history to determine if they think you may need an mpox test.

Q: How long will I need to isolate if I test positive for mpox?

A: One of the hardest things about mpox is that your isolation period is going to be especially long. It takes about four weeks for most people’s lesions to crust over and fall off. (You are considered infectious until this happens and fresh, healthy skin appears.) For some people, that may happen in two to three weeks, but for most people recovery takes about a month. This long isolation time means you may need to take short-term disability from work if you’ve been infected.

Q: Will I need medical care for mpox? How can I treat myself at home, and when do I need to see a doctor?

A: The good news is that most people will be able to stay at home and treat their symptoms with things like rest, fluids, calamine lotion and over-the-counter painkillers such as Tylenol or Advil.

But others may have more severe cases. In those situations, doctors can prescribe antiviral medications, such as cidofovir or tecovirimat, or may give someone immune globulin antibodies if they can’t get other kinds of treatment. People who have lesions in their rectum or mouth, or who have swollen lymph nodes, may also need support for pain management. You’ll also want to check with your doctor if you have lesions near your eye or if your lesions start to bruise or bleed. In those cases, you may need extra medical support.

Lastly, make sure you don’t touch or scratch your lesions. That may spread them to other parts of your body, increases the time they take to heal and can make you prone to additional skin infections and leave you with more scarring.

Q: Are certain people more at risk for mpox?

A: Unlike previous outbreaks, most people currently being infected with confirmed cases of mpox are those who identify as gay or bisexual men. However, cases aren’t limited by sex or sexual orientation, and it’s inaccurate to assume mpox is only transmitted among those in the LBGTQ+ community. There’s a real risk of stigmatizing mpox infections if people take such a narrow view.

Q: Is mpox a sexually transmitted infection?

A: Mpox can be transmitted during sex, and about 95% of cases right now involve some sort of sexual or intimate contact. But it’s not categorized as a sexually transmitted infection since it can also be transmitted through other ways.

Q: Can I get vaccinated against mpox?

A: The two-dose series of mpox JYNNEOS™ vaccine is currently available to anyone who:

- Lives in Illinois, including students enrolled in Chicago’s universities/colleges

- Has not previously been infected with mpox

The vaccine is recommended for those who are or anticipate:

- Having skin-to-skin or intimate contact with someone diagnosed with mpox (such as household members with close physical contact or intimate partners)

- Living with HIV, especially those with uncontrolled or advanced HIV

- Eligible for or are currently taking HIV-PrEP

- Exchanging goods or services for sex

- Sexually active bisexuals, gay or other same gender-loving men, or sexually active transgender individuals. Especially consider getting vaccinated if you:

- Meet recent partners through online applications or social media platforms (such as Grindr, Tinder or Scruff), or at clubs, raves, sex parties or saunas

- Have been diagnosed with sexually transmitted infection(s) (STIs) in the past 6 months

Q: What should I do if I live with someone who has mpox?

A: If someone in your house has mpox, have them isolate as much as possible and use their own bathroom (if that’s an option). Wipe down high-touch surfaces regularly with a disinfectant labelled as killing viruses, wash your hands often with soap and water or use alcohol-based hand sanitizer and try not to touch their dishes, toothbrushes or drinking glasses. Both of you should wear masks if you need to be around each other, and they should cover their lesions as much as possible if they need to leave their isolation area. (This can be done by wearing long sleeves and pants, nitrile or latex gloves, and even using a Band-aid on a lesion that’s on the face. They should follow these steps if they have to go to the doctor, too.)

When you live in close quarters with someone who has mpox, it’s also important to pay attention to how you’re washing sheets, towels and clothing that may have come in contact with their skin lesions. This is because mpox viral particles can dry and stay on surfaces for up to 15 days. Don’t shake out soiled linens or laundry — instead, ball them up carefully and slowly while wearing a mask and gloves, then toss them directly in the washing machine. Use hot water and any soap or laundry detergent you have available. After the hot wash cycle, the laundry is no longer infectious.

Q: How dangerous is mpox?

A: This outbreak had initially involved what’s known as the Western African clade (Clade II), which is less severe and has a fatality rate of about 1 percent. More recently, however, there has been an increased number of cases involving the Congo Basin clade (Clade I), which has a higher fatality rate. Many of those fatal cases have occurred in geographic areas where there aren’t many medical resources, which means people likely had worse outcomes than they would have in other regions of the world.

Aniruddha Hazra, MD

Aniruddha Hazra, MD, is an infectious diseases expert at the University of Chicago Medicine, an associate professor of the Section of Infectious Diseases and Global Health, and Director of the Infectious Diseases Fellowship Program.

Learn more about Dr. Hazra

Emily Landon, MD

Dr. Emily Landon specializes in infectious disease, and serves as Executive Medical Director for infection prevention and control.

Learn more about Dr. Landon.