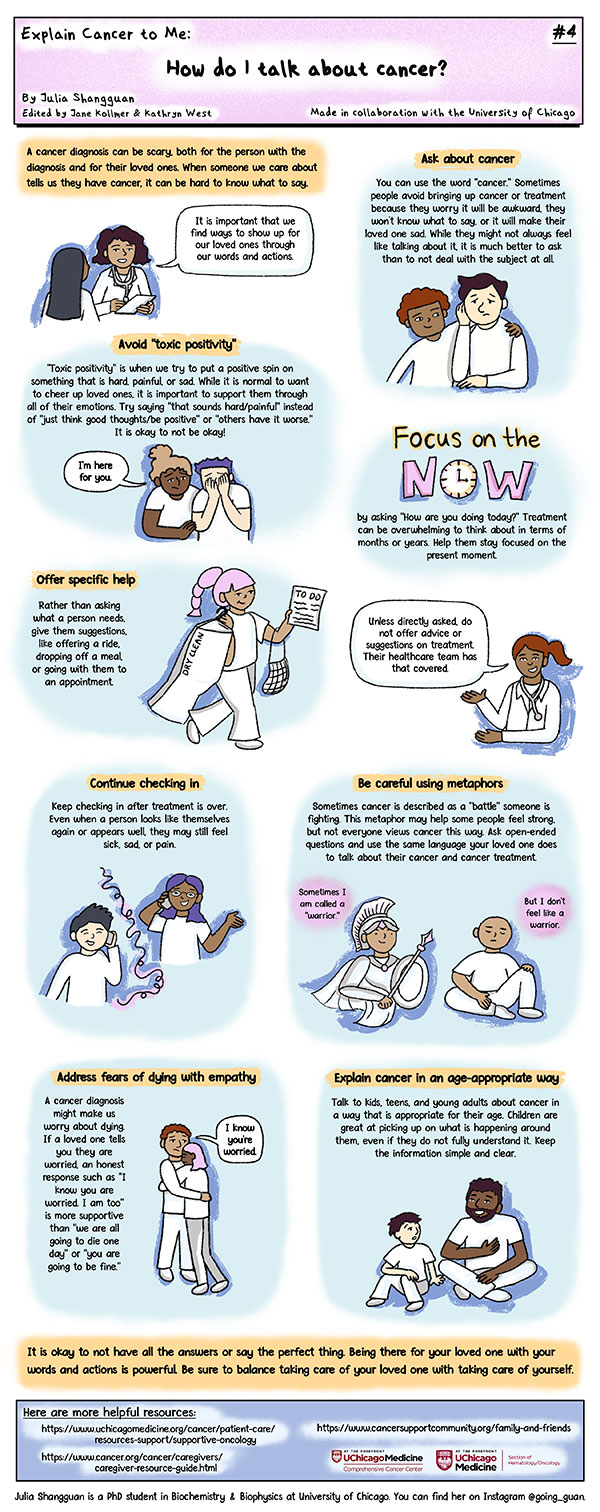

How to talk to a loved one about their cancer diagnosis

A cancer diagnosis can be scary, for the person who receives the diagnosis and also for their loved ones.

When someone we care about tells us that they have cancer, it can be hard to know what to say. It’s important that we find ways to show up for them through our words and actions, and to take care of ourselves as well.

Here are a few suggestions on how to have those hard conversations:

You can use the word "cancer" and ask about it.

Sometimes people avoid bringing up "cancer" or "treatment" because they are worried it will be awkward, they won’t know what to say, or it will make their loved one sad. While your loved one might not always feel like talking about it, it’s much better to ask than to avoid the topic.

Focus on the present by asking, "How are you doing today?"

Treatment can be overwhelming to think about in terms of months or years, so try to concentrate on what is happening with your loved one right now.

Offer specific help.

Avoid asking your loved one what they need from you.

While many of us want be supportive and helpful, asking the person what they need puts more burden on them.

Amy Siston, PhD, CST, Director of Psycho-Oncology Services at UChicago Medicine, recommends offering to do something for them by listing the suggestions you have, such as giving rides, picking up groceries, running errands or doing household chores.

Continue checking in even after treatment is over.

“Sometimes it is hard to see if a person is tired, in pain, worried or depressed,” said Siston. “Don't assume that because the person looks like themselves, that they are well.”

Try to avoid "toxic positivity."

"Toxic positivity" is when we try to put a positive spin on something that is hard, painful, or sad. It is human nature to want to make our loved ones feel better when they are feeling down, but it is important to support them through all their emotions. This might look like saying, “That sounds hard/painful,” or “I’m here for you,” instead of, “Just think good thoughts/be positive,” or “You’re so brave/strong, so you will be okay.”

It is okay to not be okay and to talk about the worries related to death and dying.

While scientific advancements in cancer treatment means that many people who receive a cancer diagnosis will live long, full lives, it can also make us worry about dying. If a loved one tells you that they are afraid of dying, don't say, "We are all going to die one day," or "You are going to be fine," or "Don't worry." Instead try, "I know you are worried, I'm worried, too," and give yourself and your loved one a chance to talk about it.

Be careful with metaphors.

Metaphors, like referring to cancer as a “battle” someone is fighting or a “journey” they are on, can give some people a sense of strength and control.

For others, these metaphors can make it harder to talk about their experience. You can try asking open-ended questions and using the same language your loved one does to talk about their cancer and cancer treatment.

Unless directly asked, don’t offer advice or suggestions on treatment.

Your loved one’s doctors, nurses and other healthcare team members have that covered.

Explain cancer in an age-appropriate way to kids, teenagers, and young adults.

Little kids are great at picking up on what is happening around them, even if they don’t fully understand it. If you are supporting a child whose loved one has cancer, be sure to talk about it in a way that will make sense to them at their age. The actual words you use will be different based on how old the child is, but for all children you should:

- Use the word “cancer.”

- Explain that cancer is not contagious and is different from being sick with a cold or the flu.

- Tell them what side effects their loved one might experience, like hair loss, vomiting or tiredness. Explain that many of these are from the medications, and not from the cancer itself.

- Give space for them to ask questions, and answer them honestly.

- Keep the conversation going. This is likely information the child or teenager will need to hear multiple times.

- Focus on any changes to their routine. For example, if their parent can no longer drive them to school, make sure the child knows who will be driving them and where their parent will be.

Remember that you do not have to have all the answers or say the perfect thing.

Showing up for your loved one with your thoughts, words, and actions is powerful! Take care of yourself.

Kathryn West is a licensed clinical social worker at UChicago Medicine who leads support groups for cancer patients.

UChicago Medicine Comprehensive Cancer Center

UChicago Medicine is designated as a Comprehensive Cancer Center by the National Cancer Institute, the most prestigious recognition possible for a cancer institution. We have more than 200 physicians and scientists dedicated to defeating cancer.

Learn More About the Comprehensive Cancer Center