In breast cancer survival rates, genetic research says genes matter

A new study is helping scientists understand a confounding disparity in breast cancer statistics.

While black women have roughly the same odds as white women of developing breast cancer, they’re 42 percent more likely to die from the disease. Now, a new study is helping scientists understand unique biological factors behind this mortality gap. And the reasons are quite different than what many researchers expected to find.

Published in JAMA Oncology in May of 2017, the multi-institutional study on breast cancer genetics and race unravels the germline genetic variations and tumor biological differences between black and white women with breast cancer. This is the first “ancestry-based comprehensive analysis of multiple platforms of genomic and proteomic data of its kind,” the authors note.

This breast cancer research is promising from both diagnosis and treatment perspectives. The findings could lead to more personalized risk assessment for women of African heritage. They may also hasten the development of novel approaches for early diagnosis and specific treatments for aggressive breast cancer subtypes.

In understanding breast cancer mortality rates, "genes matter."A key finding in the study is that black women with hormone receptor positive, HER2-negative breast cancer had a higher risk-of-recurrence score than white women. The study also confirmed that black patients were typically diagnosed at a younger age and were more likely to develop aggressive breast-cancer subtypes, including basal-like or triple-negative cancers (tumors lacking estrogen receptors, progesterone receptors and HER2), as well as other aggressive tumor subtypes.

“People have long associated breast cancer mortality in black women with poverty, or stress, or lack of access to care. But our results show that much of the increased risk for black women can be attributed to tumor biological differences, which are probably genetically determined,” said study author Olufunmilayo Olopade, MD, professor of medicine and human genetics at University of Chicago Medicine.

“The good news,” she said, “is that as we learn more about these genetic variations, we can combine that information with clinical data to stratify risk and better predict recurrences – especially for highly treatable cancers – and develop interventions to improve treatment outcomes.”

“This is a great example of how team science and investments in science can accelerate progress in identifying the best therapies for the most aggressive breast cancers,” said study co-author Charles Perou, PhD, a member of the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center and professor of genetics, and pathology & laboratory medicine at the UNC School of Medicine.

“In the largest dataset to date that has good representation of tumors from black women, we did not find much difference between the somatic mutations driving tumors in black and white women,” he added. “Yet black women were more likely to develop aggressive molecular subtypes of breast cancer. Now we provide data showing that differences in germline genetics may be responsible for up to 40 percent of the likelihood of developing one tumor subtype versus another.”

The study used DNA data collected from 930 women – 154 of predominantly African ancestry and 776 of European ancestry – available through The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), established by the National Cancer Institute and the National Human Genome Research Institute. The researchers combed through the data methodically, looking for racial differences in germline variations (normal DNA), somatic mutations (tumor acquired), subtypes of breast cancers, cancer tumor genetics, survival time, as well as gene expression, protein expression and DNA methylation patterns.

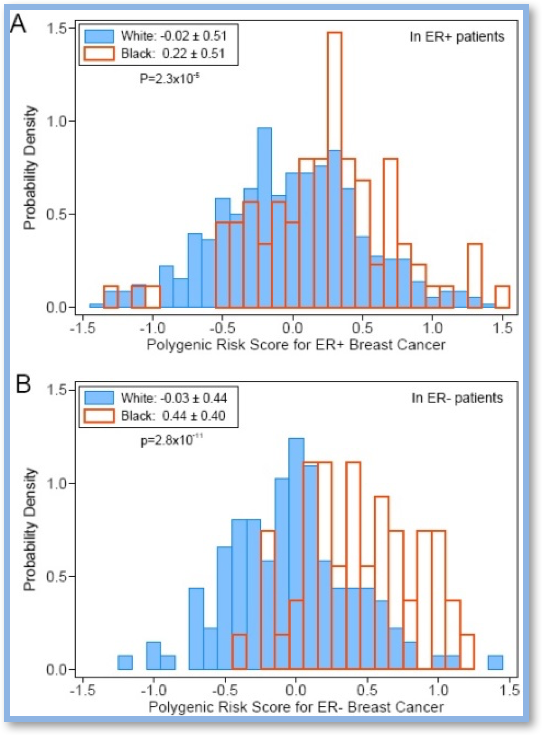

“Most significantly, we observed a higher genetic contribution to estrogen-receptor negative breast cancer in blacks,” explained first author Dezheng Huo, MD, PhD, associate professor of public health sciences at the UChicago Medicine.

Simply put, due, black women were more likely to get these highly aggressive cancers. This study is one of the very first to connect cancer tumor genetics to the racial difference in tumor subtype frequencies.

The study also revealed 142 genes that showed differences in expression levels according to race. One gene, CRYBB2 (Crystallin Beta B2), was consistently higher in tumors from black patients within each breast cancer subtype, as well as in normal tissues, suggesting it may be a race-specific gene.

The breast cancer statistics in the study revealed something else about breast cancer genetics to researchers: Somatic mutations in 13 genes or DNA segments that differed in frequency in tumors from black and white women. One of them, a mutated gene called TP53, was more common in black women (52%) than in white women (31%) and was a strong predictor of disease recurrence.

“Despite the relatively short follow-up time in the TCGA dataset, we were able to detect a significant racial disparity in patient survival using breast cancer-free interval as the endpoint between patients of African and European ancestries,” said co-first author Hai Hu, PhD, vice president for research at the Chan Soon-Shiong Institute of Molecular Medicine at Windber. “Most of the worst outcomes came from basal-like subtype breast cancer patients of African Ancestry.”

“Black women in all categories, including the most common breast cancers, were likely to have a worse prognosis,” Olopade said.

“Understanding the basic, underlying genetic differences between black and white women, the higher risk scores, and the increased risk of recurrence should lead us to alternative treatment strategies,” said Perou.

So what’s the key takeaway that can inform breast cancer detection and treatment in the future?

The crucial long-term benefit of this study, according to Olopade, is that “it’s a step toward the development of polygenic biomarkers, tools that can help us better understand each patient’s prognosis and, as we learn more, play a role in choosing the best treatment.” “Genes matter,” she added. “This is a foot in the door for precision medicine, for scientifically targeted treatment.”

“This study now outlines a path for us to personalize breast cancer risk assessment and develop better strategies to empower all women, especially black women, to know their genetics and be more proactive in managing their risk,” Perou said.

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, Susan G. Komen Foundation for the Cure, the American Cancer Society and the U.S. Department of Defense. Also contributing were Toshio Yoshimatsu and Jason Pitt from the University of Chicago; Katherine Hoadley and Melissa Troester of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Jianfang Liu, Yuanbin Ru, and Lori Sturtz from the Chan Soon-Shiong Institute of Molecular Medicine at Windber, Windber, PA; Suhn Rhie of the University of Southern California; Eric Gamazon of Vanderbilt University; Andrew Cherniack from the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard; Tara Lichtenberg from Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio; Carl Shelly from the University of Wisconsin; Christopher Benz from the Buck Institute for Research on Aging, Novato, Calif.; Gordon Mill from The MD Anderson Cancer Center; Peter Laird from the Van Andel Research Institute, Grand Rapids, MI; and Craig D. Shriver from the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, MD.

Olufunmilayo I. Olopade, MD

Dr. Olopade is an expert in cancer risk assessment and individualized treatment for the most aggressive forms of breast cancer, having developed novel management strategies based on an understanding of the altered genes in individual patients. She serves as the director of the Center for Clinical Cancer Genetics.

See Dr. Olopade's profile