The microbiome and the midnight snack: How gut microbes influence the body's clock

Poor sleep has long been linked with changes to the metabolism. Disruption of the body's internal clock can lead to changes in appetite and cravings for unhealthy food, which in turn leads to more serious health problems like obesity, diabetes and heart disease.

New research from the University of Chicago highlights a third component to that cycle: the millions of microbes that live in the intestines. These organisms respond to the same environmental cues as their host organism; their activity and metabolism is intertwined with the sleep/wake cycles and feeding schedules of the animal.

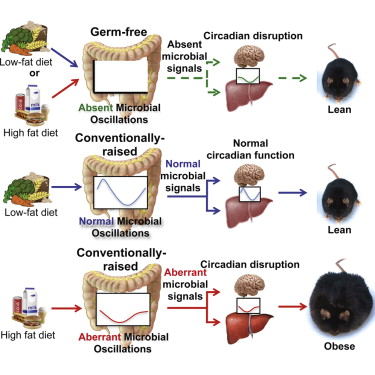

In the study, when mice were fed a high-fat diet, the patterns of activity of these microbes changed, which altered the expression of genes related to the circadian clock in the liver. These mice started eating at the wrong times and became obese, while those fed a high-fiber, low-fat diet kept their normal rhythms and gene expression, and remained lean.

While this may seem obvious -- of course the high-fat diet led to obesity -- mice that were raised germ-free, i.e. they had no microbes in their gut, stayed lean no matter which diet they were fed. This suggests that the important link between diet and its ultimate effect on body weight was the change it caused in the gut microbes.

"If the host is eating at the wrong time, the microbes can adapt to that, but it throws off their timing," said Vanessa Leone, PhD, a post-doctoral scholar at the University of Chicago and lead author on the study. "So now the host has to deal with signals from these microbes when it's not used to dealing with them, and then that's what leads to the development of obesity."

The study, published in the journal Cell Host & Microbe, was done in collaboration with Leone's colleagues from the lab of Eugene B. Chang, MD, the Martin Boyer Professor of Medicine. Chang is a leading expert on how the gut bacteria interact with the body and contribute to the development of disease. In 2012, for instance, he published a study showing that a high-fat diet can trigger inflammation in the intestine, altering the gut microbiome in ways that can lead to autoimmune diseases like inflammatory bowel disease. Studies like these show how these microbes both shape health and respond to their environment.

"We view the microbes as a sensory organ. It's not truly an organ, but it's exposed to a lot of the things that host is, so it has to adapt and change as much as the host is changing," Leone said.

The new research brings up the tantalizing possibility that these microbes could be manipulated to reverse the changes wrought by an unhealthy diet or poor sleep schedule. People can't be raised germ-free like those mice that stayed lean no matter what they ate. But if scientists figured out what a "healthy" microbiome looked like, could they develop a pill with the right mix of microbes to fix it when we have too much late night pizza? Don't give up on a healthy diet just yet, Leone said.

"We're not quite at the point where we can offer advice as to how to prevent these things from occurring," she said. "But what we do know from our data is that eating a low-fat, high fiber diet is definitely more beneficial than taking in just a high-fat diet by itself."